- About Archives

- About SAA

- Careers

- Education

- Publications

- Advocacy

- Membership

Preservation is a core function of archives management. Ideally, preservation concerns are considered as an integral component of all archival issues, functions, and decision making. As stated previously, preservation is inherent in the very idea of gathering together archival and manuscript materials for administrative, legal, fiscal, evidential, and historical research purposes. While it is possible to think of the physical and the intellectual as separate spheres of archival concern, they function best in unison. Preservation of traditional record formats largely addresses records as physical objects, with concerns focused the condition and format of collection materials, their chemical stability, the level and type of use they receive, and the effects of the surrounding environment on them. The preservation of electronic records expands some preservation challenges toward systems that ensure the persistence of and access to data over time.

In the past, management of archives was approached primarily from intellectual and functional perspectives, though format (such as motion picture film or sound recordings) has often been the basis for segregating records into special collections or administrative groups. Materials typically are appraised in terms of informational content and evidential values, arranged according to their administrative relationships, described as intellectual entities, and provided to researchers in discrete units as sources for historical inquiry. The same intellectual criteria are applied to electronic records, though obviously maintaining electronic files is very different than preserving records as concrete physical objects.

The sections that follow in this module discuss approaches to developing or expanding a preservation program within an archival institution (see Figure 2-1). In this context, for purposes of illustration and to emphasize preservation program elements, preservation may seem isolated from other aspects of archives management. The intent, however, of developing preservation programs is to assure that preservation concerns are considered at all stages of institutional life that affect the acquisition, maintenance, and use of archival materials. Issues that pertain to the well-being of physical collections must be evaluated during appraisal, processing, and outreach activities, thereby assuring that preservation is accorded equal consideration with other concerns. Though specific tasks may vary, similar considerations and actions are necessary when managing electronic records. Effective management of financial and human resources also requires this integrated approach.[1]

Preservation Program Elements

Figure 2-1 Various program elements will be emphasized at different times, depending on the maturity of the program, the needs of the holdings, and available resources. |

All archival institutions, regardless of size, type of repository, or affiliation, should evaluate their preservation needs and systematically implement necessary policy and program changes to achieve preservation goals. The administrative status and placement of archives and manuscript collections can vary greatly, from an independent government agency or division to a special collections unit within a university library. A business archives may be placed variously within the corporate structure, while a local history collection may be located in a public library or an historic house. Funding sources may vary, and repositories with paid staff may receive additional support from volunteer workers. Despite diversity in staffing, organizational structure, financial resources, and types of holdings, all archival institutions share the common goal of preserving historical materials. While specific strategies will vary depending upon local situations, all repositories can institute programs of assessment and evaluation as a means of identifying preservation needs. In many situations, internal self-study can be enhanced by using published assessment tools…and complemented by hiring consultants to advise in various program areas.[2]

Once the need to develop or expand a preservation program has been acknowledged, initiate the following activities:

Assign the responsibility for planning the program to a preservation professional, an archivist, or a committee. In very small institutions, this may be self-assigned. Define the tasks and include a timetable, with specific reporting dates for interim and final reports and recommendations.

Write a preservation policy or goals statement, which—when approved by top management or the board—will guide program planning, implementation, and resource allocation. The policy and goals statement will provide a philosophical framework and will confirm institutional commitment to the preservation program. It will also define the scope of responsibility and authority for the preservation program. Update this administrative framework as the program develops and evolves.

Gather data on preservation needs, existing preservation activities, and the impact of archival activities and functions on preservation of the records.

Establish mechanisms to facilitate information gathering, communication, and decision making throughout all administrative and functional units within the archives.

Utilize outside consultants as necessary to enhance or complement existing technical strengths in such areas as environmental upgrades and monitoring, and to help with preservation assessments if needed.

Assess financial resources allocated to preservation activities and determine if funds need to be reallocated to support new priorities or whether additional funding sources must be identified.

Ensure that mechanisms by which preservation program expansion or implementation will occur within the repository are clearly understood by all staff, and that everyone understands their own responsibilities for preservation of the holdings.

Identify ways to inform researchers, the general public, and members of the foundation or board, if traditional ways of doing business are changed because of preservation requirements. This could include instituting new research room policies on such matters as copying records, or could relate to changed exhibition practices.

Finally, once a preservation program is formally sanctioned, it must become a line item in the budget and visible on the staff roster.

The intent is to ensure that preservation is an explicit part of the institution’s goals and included in mission statements and other governing documents. As such, responsibility for preservation must start at the top of the organization, with designated responsibility for developing and executing the program.

The first steps in planning a preservation program are to assess current conditions and practices and to establish priorities and goals. Initially, program development should focus on those activities that will have a broad positive impact across the entire archives. Attention is appropriately directed toward overall holdings, rather than individual items, to achieve maximum benefit. It is very likely that many policies and procedures basic to the development of a full-scale program are already in place, at least to a degree. For example, regular dusting of boxes and shelves and the use of appropriate quality storage materials are common in most repositories, even those that may not feel they have a preservation program. It is important to recognize these and similar actions as preservation functions because they provide good departure points for further program development.

A preservation specialist or archivist (or a committee in medium-size or large institutions) should be appointed with specific responsibility for the preservation planning effort. Ideally, these will include senior staff members who have some familiarity with preservation as well as knowledge regarding the scope and nature of the holdings and institutional policies; at a minimum, however, there should be enthusiasm, interest, and a willingness to learn. The individual or committee responsible for preservation planning should be formally appointed by the chief administrative officer or governing board, in order to engender institution-wide cooperation--and later to expedite implementation of necessary changes. Even informal efforts, however, can initiate some positive results.

The designated staff should assemble information, coordinate the planning process, and initiate review of the archives facility and its environment. Important among the first steps is to assess current practices and policies to determine the degree to which preservation is already incorporated into ongoing archival functions. The number of individuals appropriately involved will depend on the size and type of institution, and on whether or not an archival preservation program is to be coordinated with preservation planning within a larger institutional setting (such as a university library or museum) or solely within the archives or special collections department. Within larger archives where such activities as appraisal, arrangement and description, and reference are administratively separate, it will be necessary to assure staff representation from all archival functions in the planning process.

Even if acting as a committee of one, however, a single archivist can do a great deal within the repository to improve procedures and implement a viable preservation program. Such an individual is already practiced at managing diverse responsibilities, and consciously incorporating preservation concerns into daily routines should be feasible.

Link program goals to conditions noted in the preservation assessment process and the degree of need identified in each area. Timetables for program development and the associated costs may then be developed. It is useful to categorize goals in terms of their time requirements (short-term, intermediate, and long-range) as well as their financial implications (minimal, moderate, and substantial). In developing a plan of action, it is advisable to include both short- and long-term goals, and changes that require little as well as more substantial expenditure of funds and effort. Not only is such an approach realistic, but it also allows program implementation to begin immediately and to display tangible accomplishments. This is necessary to sustain staff and administrative interest and support. The process of evaluation and consensus development is time-consuming and potentially exhausting; if program changes are deferred too long, or if they seem too overwhelming, interest will wane. Once goals have been agreed upon and priorities established, they can be incorporated into the existing institutional cycle of annual budgets and work plans.

If necessary, focus immediate attention on making necessary changes in the way archival materials are handled and processed. Improvements in these areas may require staff orientation and training and the acquisition of supplies, but the actual outlay of funds should be minimal. An equal priority is optimizing environmental conditions with the existing infrastructure, monitoring conditions, and then deciding what further improvements are necessary. Major changes in the infrastructure are likely to be costly and require several years (and perhaps a capital campaign) to attain. Though here, too, however, it is possible to identify such short-term goals as turning lights out in stacks, improving housekeeping practices, or installing ultraviolet light filters in exhibit spaces that will positively impact the environment in which records are stored and used. Another priority is to evaluate the facility from top to bottom—roof to basement--to identify and minimize risks to the collection. This is often done as part of developing an emergency preparedness plan, but is closely linked to environmental and physical plant issues. Attention to the building envelope and systems and implementing improvements as feasible often represent minimal cost and may in fact result in energy and other savings.

Developing in-house reformatting or conservation laboratories is generally not an immediate priority for most institutions and may not be warranted at all. In this as in other areas, program implementation must be gradual and keyed to demonstrable need as well as the ability to meet professional and technical standards. Much good can be accomplished by incorporating basic preservation procedures into archival processing; however decisions about the development of laboratories are better left until intermediate steps have been fulfilled and the repository has a sound overall program of preservation management. Commercial services can be sought to supplement in-house capabilities, though this approach—and the means of effectively managing and paying for it—must be integrated into the preservation plan.

During the data-gathering and evaluation process, issue regular reports to keep administrators and staff informed of progress and reminded of the importance of having a preservation program that is integrated with other archival functions. In addition, prepare a final statement of findings and recommendations. It is often useful to circulate such documents first in draft form; this approach minimizes the possibility of making costly mistakes and also broadens the base of institutional involvement (and thus investment) in preservation. Since proposed goals will have policy and financial implications, the concurrence of archival managers, the chief administrative officer, and/or the governing board is more likely if the point person or committee presents its findings within the framework provided by the institution's mission statement and other policy documents. Of course, reviewing such governing documents as mission and vision statements and strategic goals for the presence—or omission—of specific reference to preservation is a critical point of departure. If preservation is not visible in these documents, it should be.[3]

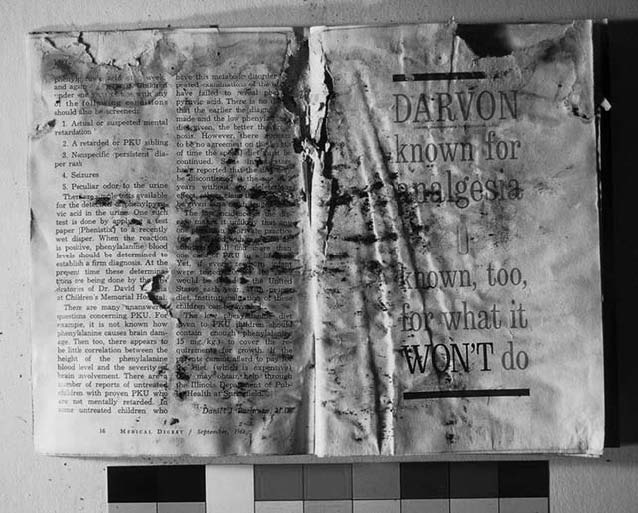

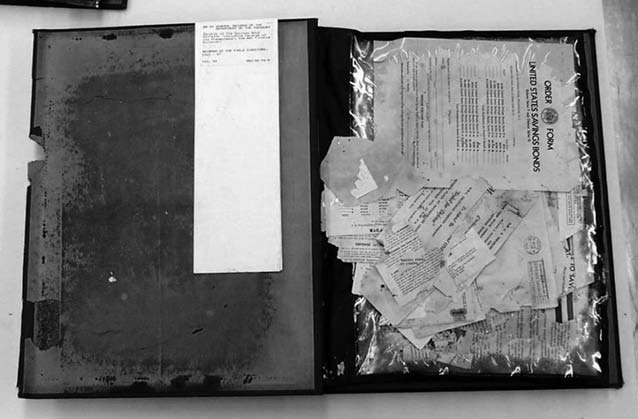

Reports and recommendations conveyed to administrators from preservation advocates may not be enough. If necessary, several approaches to further persuasion may prove effective. Tours of the archives to show examples of deterioration or poor storage conditions, especially in highly valued or visible collections, may help make the point, as well as offer an opportunity to present data on the causes of deterioration and the costs of remedies (see Figure 2-3). Examples of preservation programs at comparable institutions may provide further impetus. Fully integrated preservation programs are much more common at major institutions today than they were several decades ago. The presence or absence of a viable preservation program may also have an impact on the professional accreditation of an institution as well as on its ability to acquire grant funding or even to compete for donations of collection materials.

Once a preservation policy is approved, it is necessary to create the administrative apparatus to make it work. This may require reorganizing staff or functional responsibilities, writing position descriptions, hiring new staff, and developing written guidelines, procedures, and standards. Staff training and orientation also will be needed. Existing policy or program statements that govern other areas of archival activity (such as appraisal or exhibition) may have to be revised to conform to the newly adopted preservation policy. It may also be necessary to redefine and formalize lines of communication, consultation, and reporting between functional units or activities. For example, if not already present, it may be necessary to incorporate a preservation review into the accessioning process, as well as a preservation review of all items before they are approved for exhibition or loan. This process of assessment and refinement will result in preservation and archival policies that are consistent and formally integrated within the institution.

Be realistic in setting time-based goals. Establishing new procedures, reaching consensus, and realigning priorities and resources are difficult, and time-consuming. All change is hard, but for some staff and administrators it is an almost insurmountable obstacle. The tendency to dig into one’s position, resist change, and invoke the, “but this is the way we’ve always done it” chant is understandable. Persistence and sustained effort on the part of enlightened staff and administrators will eventually make a difference and effect necessary change.

A sound archival preservation program is based on a thorough understanding of

the building, physical plant and environment that provides the protective envelope surrounding collections;

the media, formats, condition, and extent of collection materials;

archival procedures and policies; and

the institution's organizational structure.

Once data are gathered regarding the structure and environmental conditions, the scope and character of holdings, storage capabilities, and archival processing procedures, it is possible to compare present conditions against developing preservation standards.[4] As a result of such self-study and evaluation, a preservation needs assessment statement can be written and used to design a preservation program that can be developed incrementally over time.

Preservation surveys should begin at the repository level to evaluate existing policies, programs, and activities. Once all pertinent data are broadly assembled it is possible to focus systematically on specific program elements. In order to tap into knowledge and skill of staff, and to break the data collection into manageable units, the questions can be organized under several broad headings. Develop questions that are customized to the nature and mission of the repository and its holdings. Gathering information in response to such questions as the following provides a useful starting point.

Is preservation mentioned in the mission statement?

Are there strategic goals related to preservation?

What percentage of the budget is devoted to preservation?

What is included in this category?

Have grant funds been sought or utilized to implement preservation projects?

What is the nature, range, and extent of material held by the repository? What are the predominate date spans, media, and formats?

What is the overall condition of the collection?

Are copies used instead of originals for items of high value or that receive heavy use?

Are preservation master copies created for unique items such as audio, video, and motion picture film?

Have any groups of unstable materials—such as cellulose nitrate film or Thermofax® copies—been identified? Have they received preservation attention?

Have high value items been segregated from the rest of the collection to meet security requirements?

How are various record materials and formats housed? Do housing materials meet preservation requirements? Is suitable storage furniture of appropriate design and composition available to accommodate records in various formats and dimensions?

How and for what purposes are collection items used? Is information available on the amount of use received by various items or groups of records over the course of a year?

What are the environmental conditions in areas where records are stored, handled, used, and displayed?

Are environmental conditions monitored and recorded?

Are there persistent or recurring problems with the building, such as leaks or flooding?

Are there problems with insects or other infestations?

What security provisions exist within the repository?

What fire detection, alert, and suppression systems are in place?

Is there a water detection and alert system?

Are all systems operational? Are systems inspected annually and on a regular schedule of preventive maintenance?

Do staff recognize their role and responsibilities in preserving the collections?

Does the archives have a trained preservation staff? Preservation administrator? Conservator? Photographer with preservation training?

Are staff members and volunteers trained in proper ways to handle, use, and store archival materials?

What percentage of staff time per week is devoted to preservation activities?

Does the institution have an emergency preparedness plan that is reviewed and updated on a regular basis? Are staff members periodically oriented to elements of the plan?

Are researchers monitored at all times? Are they instructed regarding safe methods of handling archival records?

Are original archival materials exhibited?

Are reformatting and duplication services available for various record formats? In-house or on a contractual basis? How have such services been evaluated?

Is conservation treatment performed on archival records? In-house or on a contractual basis? How have treatments been evaluated?

Responding to such questions as the above and gathering all pertinent in-house support materials will assist in directing attention to current preservation practices as well as to areas of deficiency and need. Existing administrative directives, preservation policy statements, and procedural guidance or manuals on such topics as housing and handling records should be assembled for evaluation, as well as available data on environmental conditions, position descriptions, emergency preparedness plans, contracts for preservation services, and budget data on preservation expenditures. Acquiring similar information and planning documents from other institutions for comparative purposes also can be helpful.

Preservation surveys must be specifically grounded within the context of the institution, its holdings, the relative values of collections, and the ways in which materials are used. For these reasons, it is important that staff familiar with the holdings and physical plant be intimately involved in the planning process, data-gathering, and evaluation of results. For example, experienced staff will know exactly which stack area is susceptible to leaks every spring, and will also know the institutional hierarchy of research, monetary, and intrinsic values assigned to the collections.

Programmed self-study models have been developed to guide institutions through preservation needs assessment.[5] However, this is not to say that staff should undertake surveys without the assistance of outside help. Also, since many areas that need to be evaluated--such as building structures, air handling systems, and environmental conditions--are extremely complex, the services of outside specialists may be necessary to accurately assess existing conditions and propose options for improvements that are appropriate, technically feasible, and energy efficient.

Consultants can be hired to undertake specialized portions of the needs assessment. They can offer sound technical advice and an important point of departure. The institution must provide the programmatic context within which site visits and surveys will be most effective, and staff must therefore be prepared to devote sufficient time to planning and preparing for the consultant's visit. Visits by outside consultants are usually of short duration, sometimes only a day or two, though arrangements also can be made for periodic follow-up visits to work through particular issues. Whether surveys and assessments by consultants are global or specifically focused—for example on achieving efficiency in the air handling system or conducting a condition assessment of a group of photographs--it is up to institutional staff to utilize the data and recommendations provided to work toward necessary changes and improvements.

Thus, the role of internal staff responsible for preservation planning is critical. They must interact with consultants, define the focus of their visits, provide them with background information, analyze the recommendations received, and initiate program improvements. Outside consultants can provide invaluable technical assistance to complement the staff's knowledge, and their recommendations may carry more weight than the staff’s with administrators or governing boards. Also, it is increasingly the case that granting agencies require (and often provide funding for) institutions to have undertaken general preservation surveys conducted by qualified consultants before they will consider funding specialized projects.[6] Despite the important role consultants can play, however, it is up to the institution and staff with ongoing preservation responsibility to sustain the effort.

Following a review of repository-wide conditions and policies, attention should be directed toward the needs of the archival holdings, especially for improved housing, reformatting, and identifying unstable materials (see Figure 2-3). There are different approaches to compiling this information. One approach is to undertake periodic surveys that through appropriate sampling techniques permit the compilation of data that characterize the condition and preservation needs of the holdings in their entirety. Sampling techniques can be devised with assistance from a statistician to determine how many units need to be surveyed in order to acquire data that has a high level of confidence in the accuracy of the information. Depending on circumstances, such broad institution-wide surveys might need to be redone every ten years.

Broad surveys tend to broadly characterize the overall state of the holdings. While this is useful for planning purposes, surveys typically do not provide specific information on the condition and needs of individual collections or groups of records. Undertaking preservation risk assessment is one method that can be used to acquire the more specific information that is needed to plan preservation projects and establish priorities among collections. This approach permits the integration of data-gathering with ongoing archival functions, which is an efficient use of staff time. For example, risk assessment forms can be filled out during accessioning or processing activities, and researchers can be encouraged to report to staff potential preservation problems that they encounter.

Whether information is gathered in a dedicated statistically valid survey that provides a representative overview of the preservation needs of the entire holdings —or if data is acquired on individual collections over a period of time as part of other archival duties--such data provides the basis for short- and long-range preservation planning. However, since circumstances change—use patterns alter, new collections are acquired, and preservation work is accomplished—survey data and risk assessments will need to be periodically refreshed.

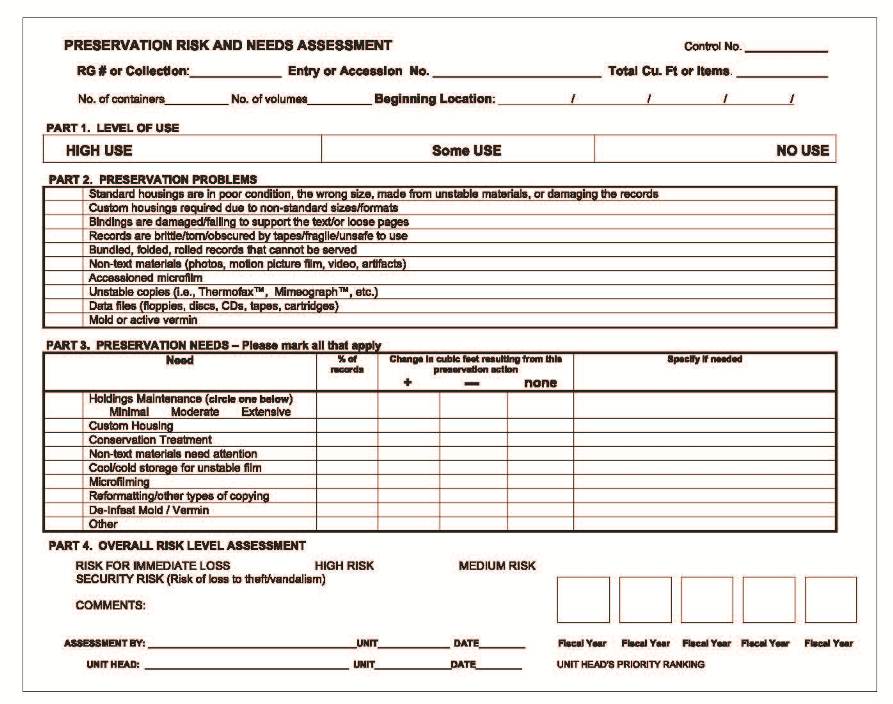

To expedite the gathering of risk assessment information, design a form or checklist that is easily understood and simple to fill out (see Figure 2-4). Gather information in such areas as:

types of material (formats and media),

general condition,

evidence of damage,

evidence of chemical instability,

quality and suitability of housing,

whether preservation or duplicate copies exist,

value, and

extent or level of use.

Carrying out risk assessment permits repositories to quantify their preservation backlogs and initiate programs to address them. In addition, risk assessments help to identify preservation needs that must be addressed immediately versus over time, and provides a mechanism for establishing priorities for preservation attention. Assessment forms should have a comments or notes field to permit preliminary description of materials that require technical identification or further evaluation at a later date. This may be true for some photographic materials, including potentially unstable film bases, as well as other media—such as sound recordings--that require evaluation by a specialist. In such cases, the assessment forms can at least note the existence and location of potential problems.

Train staff members conducting risk assessments (or broad condition surveys) to recognize the physical characteristics of the materials they are most likely to encounter; they should not be expected to make definitive determinations of chemical stability. Rather, the emphasis should be on identifying common types of material, recognizing improper housing, evaluating condition, and noting evidence of instability. Clues in the latter category include odors; cockling or other dimensional distortion of film; diminished contrast between text and background (i.e., fading of text or darkening of paper) that affects legibility; and migration of stains to adjacent items. Information on the overall condition of collections should be gathered broadly to convey a proportional sense, for example, of the percentage of paper tends to be brittle or the percentage of bindings that are damaged. Such information can be used in the short term to trigger basic preservation responses (placing weak paper in polyester sleeves or tying or boxing bound volumes). Over a longer term, assessment forms that note condition problems may trigger the need for a more detailed survey by a conservator and may, perhaps, lead to a decision to carry out conservation treatment or reformatting.

Design the risk assessment and/or survey tool to ensure—to the degree possible—that each collection is reviewed from the same perspective. Since many of the categories to be addressed are subjective, train staff to have common understandings of terms and condition problems. Written definitions and illustrated guidelines will help orient staff and also will provide documentation over time of the approaches used. To help ensure consistency and accuracy, it is useful at the outset of a survey or assessment project to conduct trial runs. Have all participating staff review the same sample groups of records, independently fill out survey forms for each, and then compare results. Discrepancies in assessing materials can be discussed, which should help to eliminate them in the future. Also, as a result of the pre-test and subsequent discussion, refine the forms as necessary to clarify intent and avoid confusion.

Since most repositories are not static, surveying and assessing collections should be an ongoing activity as new accessions are received and research and use patterns change. Retrospective attention should focus on parts of the holdings that are heavily used as well as those known to contain unstable materials or other preservation problems that inhibit access. Once a body of data is assembled, it can be used to develop priorities for a variety of preservation actions.

Once data has been gathered from repository-level surveys and preservation needs assessments of the individual collections and holdings, it is time to establish priorities for action. It is likely that multiple activities will be identified that can move forward simultaneously. These activities can be both on broad program and policy fronts as well as on collection-level projects. As noted above, repository wide improvements might include upgrading environmental conditions or procuring cold storage for selected segments of the collection. It may take time to identify funding for such projects. But while working for necessary funds, progress can be made in developing or updating preservation policies, guidelines, and directives. The latter activities may require a reallocation of staff resources and shifting of other institutional priorities, but little in the way of actual funds.

Establish collection-level preservation priorities by analyzing the data gathered and ranking records based on risk level. Will information be lost or records be further damaged if they continue to be used without preservation intervention? Use of the records is a critical factor in this decision making process. Data on actual or estimated patterns of use—and the nature of that use—can be used to further refine and develop preservation priorities. Other factors to weigh in establishing preservation priorities include the relative values assigned to materials as well as available institutional resources.

The impact of use as a trigger for preservation attention will vary across the collections. For example, seldom used textual records that rest passively in suitable storage conditions typically are not high priorities for preservation attention based on use. However, collections that receive a high level of staff or research use and handling are likely to be very important to the institution and may also be in the poorest physical condition because of the high degree of handling they receive. In such situations, use is an important motivation for action, as it is for records that are so vulnerable that they cannot withstand even one additional use without damage.

While use and potential use are always worth evaluating, some actions must be taken regardless of actual or projected use if the records are to survive. For example, format, deterioration, and/or equipment obsolescence are primary triggers for preservation attention with certain audio visual and electronic records. Similarly, chemically unstable films that have a short timeline for survival require intervention—such as cold storage—independent of use considerations. However, knowledge about use levels in such situations will still provide helpful data in setting priorities, in scheduling reformatting or duplication, or undertaking archival processing.

For use to be applied as a factor in preservation decision making, it is necessary to define what constitutes use level in the repository. Since preservation decisions are usually applied uniformly across a related body of records, it is good to think of use broadly in this context. Depending upon the type of institution and its holdings, use may be considered across an entire series, entry, record group, or manuscript collection. Also, it may be appropriate to define use levels differently for different media types, knowing, for example that the impact of use on films is different than on paper.

High - 5-10 times per year Medium - 2-5 times per year Low - less than once per year

The above is simply a point of departure for thinking about specific use patterns and levels. Use data can be averaged over several years to create a more accurate picture and to take into account anniversaries and similar special events that may spike research activity in particular groups of records. The type of use is also a factor. Are specific records within a group handled often by staff in responding to reference inquiries? Do researchers regularly handle the same body of records in the research room? Is the use an exhibit, or possibly sending the same records repeatedly for duplication? Ideally, the various types of use will be documented via charge and pull slips or similar documentation. If it is not, archival staff will need to make their best judgment about use level, based on their knowledge of the holdings. Regardless of how the number is reached, shared definitions must be used to transform the number into a use ranking.

Archival materials may be regarded from a number of perspectives, and values attached accordingly. Intrinsic value, which usually relates to the physical attributes or associations of a document rather than its intellectual content, is important in this context.[7] Artifactual value must be considered in addition to informational value. Is the physical form a subject for study? Does the item have artistic or aesthetic merit? Does it have exhibit potential? Records that have intrinsic value are normally maintained in their original format, though they may be ideal candidates for copying or reformatting to preserve their informational content and protect the originals from handling.

Age is another criterion, on the assumption that early records are scarce and thus take on added significance. Some records convey legal rights and obligations that may require retention in original formats, and records of suspect authenticity must be maintained in original form so that they may be physically examined and analyzed. Records relating to the establishment of an organization or institution—charters or constitutions, for example, or papers relating to the founder—generally have high value, as do records that relate to the primary collecting focus of an institution.

Though typically institutions do not appraise their collections from a monetary perspective, the market value—and the potential for theft—must be taken into account when considering the relative values inherent in the collections as a whole. As with use, agreed-upon criteria must be used by the repository when establishing relative values. Enhanced security measures can be applied accordingly, and value can be taken into account when establishing priorities for preservation action. Value is also a consideration when it is necessary to establish priorities for salvage during emergency response operations.

Any repository likely has materials that were acquired before there were well-defined collecting policies or when the archives was new, with a seemingly never ending range of empty shelves. With the passage of time, the refinement of collecting policies and appraisal criteria, and perhaps the growing scarcity of storage space, some collections acquired early may not meet current selection standards. However, given the difficulty of deaccessioning materials (or the effort required to do so), they often remain taking up scarce real estate, unused by staff or researchers. While such collections passively reap the preservation benefit of good environmental conditions, they may never warrant rehousing or other active preservation intervention because of their limited value to the repository. Such materials may be candidates for off-site storage.

Consider the chemical stability of records when setting preservation priorities. Unstable film-based materials that are actively deteriorating and posing threats to other materials may require cold storage or in some case duplication before information is lost (see Figure 2-5). Records that are wet or that are actively moldy or infested are in immediate danger of loss and require emergency preservation intervention.

All of the above factors must be weighed in determining, in priority order, which collections require immediate preservation attention--which can or must be copied, rehoused, placed in cold storage or receive conservation treatment--and which can either safely await future action or never receive overt attention at all. Given the heterogeneous nature of archival materials, there is no standard formula that can be applied uniformly across the holdings to assess the relative values and preservation needs of collections. Further, classes of material need to be evaluated separately, since paper, film, audio materials, and electronic records all have their own critical path of deterioration and need for preservation intervention. Thus, criteria for implementing preservation plans and actions will vary from institution to institution, each developing its own set of factors to evaluate unique collections.

Once you know where you are it is possible to decide where you wish to go and how to get there as expeditiously as possible. It is clear that considerable energy must be expended before responsible preservation decisions can be made. Information must be gathered, organized, and analyzed on the preservation needs of the holdings and the relative values of collections. All of this must be balanced against financial and staff resources and available technical expertise. Planning must not become an end in and of itself, however, deferring action while forever pondering where to begin, or consuming resources that might be more productively utilized in caring for the collections. One approach to managing this seemingly daunting body of information is to think in terms of preservation systems. These systems can be broad areas of activity that are defined separately but bear synergistic relations to one another. For example, improving environmental conditions is a defined set of activities, as is improving the housing of archival materials. Each activity on its own will greatly enhance the useful life of collections, but in combination the benefit is even greater.

Preservation systems that can be considered as starting points include: environmental control, storage and housing, handling and use, and duplication and reformatting. Each of these contains possibilities for action that include short- and long-term goals and a range of financial implications. Thus, it is possible to select starting points within each system, depending on needs and resources. Preservation professionals generally agree that it is wise to undertake first those preservation program activities that will have the broadest impact on the entire holdings. For most institutions, this means improving environmental conditions, which is easily the most expensive and difficult of preservation undertakings.

Therefore, an approach that encourages the initiation of efforts (and perhaps fund raising) to improve the environment, such as monitoring and recording environmental conditions, while at the same time instituting preservation training for staff and the rehousing of records, will permit progress on several fronts simultaneously. During the course of a year, environmental monitoring can provide the documentation necessary to influence funding allocations, while staff training and rehousing initiatives will achieve immediate benefits for the holdings.

Preservation decision making at the collection level involves deciding among collections (which ones present the greatest priority for attention?), as well as deciding what the appropriate actions are for a given collection. Ranking preservation priorities takes into account relative importance and value, actual or anticipated use of collections, and condition and degree of need. Dealing with records at risk of immediate loss is the highest priority. Unstable records that must be put into cold storage or duplicated or reformatted before information is lost normally represents a critical, high priority need. Below that, high, medium, and low priorities will evolve based on use and the other factors mentioned above.

When evaluating the appropriate preservation actions for an individual collection or body of records, intrinsic value is one factor to consider, in addition to responses to such questions as:

Are the records in stable condition? Can they be handled safely?

What type of use do the records receive?

What level of use do the records receive? If heavily used, have they been reformatted?

Are damaging or poor quality enclosures present? Do they inhibit safe access to the records?

Responses to such questions will form a profile of preservation need and appropriate options for preservation attention. Some records will have needs in multiple areas (such as holdings maintenance and reformatting). Collectively these data can be used to rank projects in priority order within each action category.[8] Staff, technical capabilities, and financial resources will determine what projects can be accomplished in-house, and which will require outside assistance. A flow chart can provides a graphic example of such preservation decision making.

The amount of money that should be budgeted for preservation activities will depend on the size and needs of the collection, the number of discrete program areas, and the number of staff members with sole or partial preservation responsibility. Costs of supplies, equipment, and services also must be calculated. Unfortunately, according to the results of the Heritage Health Index survey, relatively few U.S. institutions regularly designate funds to conservation/preservation, and for those that do, the budget for this category is relatively low. The report states, “Lack of financial support is at the root of all the issues identified in the Heritage Health Index. Making funds for preservation a consistent and stable part of annual operating budgets would begin to address these issues”[9] Almost one-third (30%) of the institutions reporting had no funds budgeted for preservation, while 38% of the respondents had a preservation budget of less than $3,000. [10]

A reasonable—though seemingly not often attainable-- goal, however, is to allocate approximately 10-15 percent of the total archives budget for preservation (i.e., that portion of the institutional budget allocated to support archival or custodial functions and responsibilities). Funds budgeted for preservation should grow incrementally on an annual basis to reflect and support program development and expansion until a mature program is achieved, at which point major budget growth would level off.

In order to make progress, the preservation program must receive consistent, ongoing institutional support. If there is not a known amount of money available for preservation activities, it is impossible to plan, set priorities, purchase supplies, or even designate staff with specific preservation responsibilities. For most institutions, preservation problems are too great to expect miracles from piecemeal or haphazard approaches, and it is unrealistic and inappropriate to expect that external funding organizations will support a preservation program in its totality, or even specific preservation projects or initiatives indefinitely.

Budgeting for preservation can begin by evaluating the total archives budget and determining what proportion of monies are expended under such broad categories as personnel and compensation, space and physical plant, utilities, and supplies and services. The focus should then be narrowed, to the degree possible, to expenditures related to supporting basic archival functions, such as maintaining and housing records, arrangement and description, providing reference service, and duplication and reformatting. Within these categories it should be possible to identify preservation-related supplies, services, and personnel costs. Assigning costs to the appropriate function is sometimes difficult. For example, an in-house photography laboratory may carry out both preservation duplication and fee work for clients, while file folders and boxes enhance the preservation of records and at the same time expedite reference and access. In each program area calculate the proportion of activity (and thus funds) devoted solely or primarily to preservation. Given the importance of suitable housing to the preservation of records, it seems reasonable to assign all costs for boxes and folders to preservation, although internal budgeting dynamics may affect whether this is practical. Of necessity, some assignments will be arbitrary, but the goal is to unite all preservation-related expenses under one entry. Assembling such expenses as purchasing archival housing materials or data loggers and subscribing to preservation publications provides evidence that preservation activities do in fact exist, even if they are not yet formalized in a programmatic context.

Preservation Program Budget Elements

Figure 2-7 Funds allocated in each area will depend on annual preservation program initiatives. Some categories represent recurring expenses while others represent one-time or periodic expenses. In some institutional accounting systems, certain expenses may be assigned proportionally to several program areas. |

Somewhat more difficult is acquiring additional funds to meet the goals of a new or expanded preservation program. The degree of support will depend on the administrative commitment to preservation and on overall institutional acceptance of the program goals. Funds requested to support preservation activities should be keyed to the goals articulated during the planning process and the associated timetable for implementation. Supplies, equipment, personnel, service contracts (such as for preservation microfilming or digitizing), and staff training are all potential elements in a preservation budget (see Figure 2-7) Rapid increases in funds should not necessarily be expected, since all new programs must prove their worth while competing with other institutional priorities for scarce resources.

Document successful completion of goals with regular progress reports to administrators, staff, and oversight boards. Incremental improvements in the program and the completion of special projects are worthy of attention. Activities accomplished as a result of increased or special preservation project funding—such as duplicating and rehousing glass plate negatives from the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition—may be worthy of a press release, notice in the repository newsletter, or even a small party! Such activities celebrate progress and help to assure administrators and colleagues that funds are being utilized wisely to achieve concrete results. Success stories will help to generate ongoing support.

Outside funds also may be sought to support the preservation effort. State, local, and federal funding agencies, as well as private foundations, often grant monies to preserve significant archival materials or to fund staff positions for preservation projects (see Appendix H, Funding Sources for Preservation). The archives also should look close to home for preservation funding. Donors may be convinced to provide funds to meet the preservation needs of their own collections, or to make a gift for the treatment of an item of high value. A friends group may be encouraged to support a particular preservation project through monetary gifts or special fund-raising efforts. Gifts should be publicly acknowledged (with the donor's permission) through newsletters, receptions, or the placement of plaques, though the latter can become problematic from political (and sometimes aesthetic!) perspectives. Fund-raising consumes staff time and requires ongoing nurturing and attention. The rewards can be very great, however, and also may help to increase the flow of internal funds to preservation activities. This is obviously a necessity when granting agencies require cost-sharing and other evidence of institutional support, but the value outside agencies and individuals place on the collections and their preservation can only help the preservation mission.

As stated previously, all staff members in an archival repository should have designated preservation responsibilities. All position descriptions should include requirements that records be handled carefully in prescribed ways that meet preservation goals. In addition, the repository should have a designated preservation officer. Whether this position is full-time or part-time, it achieves the goal of assigning primary preservation responsibility to at least one staff member. However, whether the position of preservation officer represents a new staff position or is simply the archivist accepting added responsibilities, it must be made a formal part of the individual's job assignment and title, with a percentage of time attached to these duties.

The administrative placement of the preservation function will vary depending upon the size and organization of the archival repository. Large repositories may have a preservation division or department with several staff having different areas of responsibility, while in small archives a part-time preservation officer may be more suitable. Archives that function as a department within a university library or museum may interact with an institution-wide preservation unit. Size and administrative placement are less important, however, than delegated authority.

If the preservation officer is to have a positive impact on the collections, the position must have status within the institution that is equal to that of policy-makers in other program areas.

The preservation officer (or program) has a number of responsibilities to fulfill or oversee. The list below is by no means exhaustive, but does give a sense of the breadth of responsibility. The duties are extensive enough to warrant a full-time position or positions in a large institution with diverse program elements, although an archivist working alone with minimal assistance can also incorporate many of these functions into work routines over time.

The preservation officer is usually an administrator or manager with responsibility to oversee a variety of technical preservation functions. The preservation officer should be knowledgeable regarding these matters but does not need to be a practitioner in technical areas. Depending upon the size of the institution, the nature of the holdings, and the development of the preservation program, the preservation officer may be expected to fulfill or oversee the following responsibilities. Program activities will build incrementally over time.

Institute preventive preservation measures. This is a policy-level responsibility that requires the evaluation of all archival activities and procedures from a preservation perspective. Ongoing review is necessary to ensure that preservation standards are maintained.

Coordinate and direct all preservation efforts within the archives. Serve as liaison with other institutional divisions or departments, including security, facilities engineers, and maintenance staff.

Monitor environmental conditions; agitate for necessary improvements. Maintain daily records of temperature and relative humidity.

Develop and conduct preservation risk assessment.

Manage all conservation treatment activities, in-house and/or contractual.

Manage all duplication and reformatting activities, in-house and/or contractual.

Develop an inventory of available preservation and conservation services and supplies, including manufacturers' and suppliers' catalogs.

Order and monitor quality of archival supplies.

Develop safe exhibit practices and procedures.

Monitor housekeeping practices.

Coordinate security program if one does not already exist.

Build a preservation reference library.

Represent the archives at professional meetings and develop contacts in the preservation community.

Plan and implement an emergency preparedness program. (Working on an emergency plan is a good way to involve the entire staff in preservation activity.)

Train staff in preservation procedures designed to safely house, handle, and prevent damage to records.

The last point deserves special attention. Staff training is an ongoing responsibility. All staff should be made aware of basic preservation philosophy, practice, and techniques as they pertain to archival materials. Training and orientation must be directed toward staff at all levels—administrators and senior archivists through student, interns, and volunteer workers—and mechanisms must be established for continued training and for orienting new staff members. A concise preservation manual or policy statement specifically keyed to the repository's procedures in the areas of storage, handling, and use of records is a helpful training aid that may be given to new staff. Lists of specific "dos" and "don'ts" are also useful, to provide guidance on such topics as what to do if damaged records are encountered, the use of pens, and limitations on copying various materials and formats. Means should be devised to encourage staff to participate actively in the preservation process. Periodic problem-solving sessions where specific topics are discussed—such as options for housing and handling oversized records—help to stimulate thinking about particular issues from preservation perspectives (see Figure 2-8). A number of excellent audiovisual and online training tools are available on preservation topics; these can provide a focus for staff training sessions[11].

There are academically trained and experienced preservation administrators that can be hired to fill preservation positions.[12] If this approach to building staff is not immediately feasible, it is important for the institution to make training opportunities available for the staff member designated as preservation officer.[13] In either case, it is vital that the preservation officer read widely in the preservation literature to keep abreast of changes and developments. The preservation officer should also join professional preservation, conservation, and imaging organizations and attend educational seminars as a further means of keeping current as well as making useful contacts. Colleagues at other institutions can provide much help and information, and visits to similar institutions with more developed preservation programs can provide valuable learning experiences.

One of the most important elements in a preservation program is ongoing review and evaluation. All activities undertaken in the name of preservation must indeed enhance the well-being of archival materials. Archival holdings and programs are ever more complex, and preservation is equally so. Misguided efforts, priorities that cannot be justified, or the implementation of technically poor procedures are likely to be costly, in terms of lost resources, the potential loss of information, or actual damage to records. They can also be embarrassing to the institution, as well as damaging to its reputation. Archives preservation is not intuitive. For all of these reasons, it is incumbent upon archival institutions to proceed judiciously in implementing preservation activities, to ensure that staff are qualified to carry out the tasks set before them, and to rely upon existing technical standards and specifications. Mechanisms should be established to monitor and assess preservation program activities, both against agreed-upon internal goals and against the external world of archives preservation as a whole. A regular schedule of program assessment will help ensure that the preservation program is indeed built upon solid ground.

* * *

The range of preservation choices are many and the variety of archival and manuscript materials are exceedingly diverse. The modules that follow will address both the nature of materials found in repositories and the approaches available to care for them.

[1] Two useful works addressing archival and preservation management are: Michael J. Kurtz, Managing Archival and Manuscript Repositories (Archival Fundamentals Series II). Chicago: Society of American Archivists, 2004, and G. E. Gorman and Sydney J. Shep, eds., Preservation Management for Libraries, Archives and Museums. Facet Publishing, 2006.

[2] Heritage Preservation, through its Conservation Assessment Program, provides professional assessors to museums and repositories to evaluate many aspects of basic preservation care and maintenance of collections. Such data can be used to develop and enhance program activities as well as seek federal grants. See The Conservation Assessment: A Tool for Planning, Implementing, and Fund-raising at: http://www.heritagepreservation.org/CAP/assessors.html The American Institute for Conservation (AIC) provides a referral service to conservators and preservation specialists who can provide consultation and assessment services; see: http://aic.stanford.edu/

[3] Concise mission statements are effective and easily become part of the working life of the institution. For example, the mission statement of the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution is succinct: “To illuminate scholarship of the history of art in America through collecting, preserving, and making available for study the documentation of this country's rich artistic legacy.” See: http://www.aaa.si.edu/about/about.cfm#mission Similarly, the mission statement of The State Historical Society of Iowa emphasizes a dual mission of preservation and education. And reads in part: “As a trustee of Iowa's historical legacy, SHSI identifies, records, collects, preserves, manages, and provides access to Iowa's historical resources. See: http://www.state.ia.us/government/dca/shsi/about/mission_goals/mission_goals.html#Vision

[4] SAA has initiated a project to develop a Trusted Archival Preservation Repository program, including a preservation self- assessment tool for gap analysis. This will serve as an authoritative source of information that can be used to help convince resource allocators of the need to address existing preservation deficiencies. For information and updates, contact SAA at http://www.archivists.org/

[5] For example, see Beth Patkus, Assessing Preservation Needs: A Self-Survey Guide (Andover, MA: Northeast Document Conservation Center, 2003). Available in print version or online at: http://www.nedcc.org/resources/downloads/apnssg.pdf

[6] Though funding priorities and projects shift over time, the following agencies are potential sources of funding to support preservation surveys: National Endowment for the Humanities, Preservation and Access: http://www.neh.gov/grants/grantsbydivision.html#preservation; National Historical Publications and Records Commission: http://www.archives.gov/nhprc/; and the Institute for Museum and Library Services: http://www.imls.gov/. Heritage Preservation sponsors the Conservation Assessment Program, which provides cultural heritage institutions (including archives, libraries, and museums) with consultants to conduct a general conservation assessment of collections, environmental conditions, and facility issues. For information, including eligibility, see: http://www.heritagepreservation.org/CAP/index.html

[7] NARA Staff Information paper 21, Intrinsic Value in Archival Material (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Service, 1982) defines the criteria to be evaluated in determining whether records have intrinsic value. These qualities or characteristics relate to the physical nature of the records, their prospective uses, and the information they contain. They include: 1. Physical form that may be the subject for study if the records provide meaningful documentation or significant examples of the form. – 2. Aesthetic or artistic quality. – 3. Unique or curious physical features. – 4. Age that provides a quality of uniqueness. – 5. Value for use in exhibits. – 6. Questionable authenticity, date, author, or other characteristic that is significant and ascertainable by physical examination. – 7. General and substantial public interest because of direct association with famous or historically significant people, places, things, issues, or events. – 8. Significance as documentation of the establishment or continuing legal basis of an agency or institution. – 9. Significance as documentation of the formulation of policy at the highest executive levels when the policy has significance and broad effect throughout or beyond the agency or institution.

[8] Key issues to consider in identifying materials for preservation are covered in The Preservation of Archival Materials: A Report of the Task Forces on Archival Selection to the Commission on Preservation and Access (Washington, D.C.: Commission on Preservation and Access, April, 1993). See http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/arcrept/arcrept.html

[9] The Heritage Health Index (HHI), sponsored by Heritage Preservation with support from the Institute for Museum and Library services, was the first comprehensive survey conducted of condition and preservation needs of U.S. collections. The survey was distributed to more than 14,500 archives, libraries, historical societies, museums, archeological repositories, and scientific research collections. The response rate was 24%, overall, with a 90% response for the nation’s largest and most significant collections. The survey elicited information on the following topics: condition of collections, environment, storage, emergency planning and security, preservation staff and activities, preservation expenditures and funding, and intellectual control over collections. Only 23% of collecting institutions, which includes archives, had special funding for preservation in annual budgets, while 36% budget for preservation through other line items, such as curatorial or technical services. To view the full report, see: http://www.heritagepreservation.org/HHI/full.html

[10] Ibid. According to the HHI, 43% of archives have annual budgets for conservation/preservation of less than $3000. Also in archival repositories, the proportion of total annual operating budgets to conservation/preservation budgets is 7%.

[11] For example, see Preservation 101, an online course offered by the Northeast Document Conservation Center at http://www.nedcc.org/education/offerings.php .

[12] Online job postings are a good place to look at position descriptions and qualifications cited for preservation staff. Useful sites to check include SAA (http://www.archivists.org/), the American Institute for Conservation (http://aic.stanford.edu/), and Conservation OnLine (http://palimpsest.stanford.edu/).